Our History

For thousands of years we have done it on clay, birch bark, papyrus, sheepskin, paper, and lately in electronic media: drawing pictures and writing down our thoughts for own delight and information, and to share with others what’s on our mind. In the earliest days of Northfield, Vermont, folks eagerly borrowed and loaned books, newspapers, and magazines. Reading–or being read to, if you couldn’t read–was essential for entertainment and for acquiring information. In the early 1850’s a small circulating library was set up in Northfield’s recently built railroad depot on the west side of the common. Northfield was a major center for the Vermont Central Railroad, which was headed by Charles Paine, a former governor of the state and a son of Elijah Paine, a leading citizen who had built a prosperous woolen mill in town. In 1856 the Vermont and Canada Railroad Association was formed, again circulating books from the railroad depot. The photo of Northfield below, courtesy of the Northfield Historical Society, was taken from a hill west of town about 1865 or somewhat later. The railroad depot, which housed the town’s early circulating libraries, is slightly left of center.

In 1871, seventy-five Northfield citizens initiated the Northfield Library Association, paying $5.00 a share for the Association’s stock and coughing up an additional fifty cents a year for dues. Shareholders paid two cents a book to borrow from the library; non-shareholders paid ten cents a book. The railroad depot was still the literary center of Northfield, for the library was located above a train shed. Below you see the depot as it stands today, minus the wings on either side. There has always been a bank in the depot ever since it was built.

In 1895, the citizens of Northfield voted $50 to participate in the system of free public libraries, which the legislature had established the year before. Northfield’s Free Public Library acquired the assets of the old Northfield Library Association and settled into quarters in the Paine Block, a major building on the east side of the common. When a citizen paid for a license for his dog, he did his bit for Northfield culture: the dog tax went into the library’s coffers. The Paine Block burned down and the library was established in the Union Block, which burned down in 1904. Fire could not destroy Northfield’s determination to have a free public library and the books were installed in the house of a private citizen on South Main Street.

Now George Washington Brown comes on the scene. He was a Northfield boy who at eighteen started out as a timekeeper in a machine shop of the Central Vermont Railroad in Northfield. He worked his way up in grocery and hardware businesses, became an auditor for the Central Pacific Railroad in California, and eventually served as the general manager and treasurer of various firms that made machinery for shoe manufacturing, ending up as a vice president of the United Shoe Machinery Company. He had become a very wealthy and prominent businessman in the Boston area, and a patron of the arts, particularly music.

Brown’s portrait hangs over the fireplace in the north reading room, where the tables may have a puzzle to work on and a display of interesting books in the collection. Patrons can read, take notes, or work with a laptop computer at the tables.

Brown offered to build a library for Northfield for $20,000 to $25,000 dollars in memory of his grandparents, parents, and wife. The site purchased for the library was the former home of the late Charles Paine. Paine’s home was moved sixty feet north, and now houses the Northfield Historical Society. Brown supervised the design of the library, which is similar to the design of the Carnegie libraries, but which had some interesting new features, such as a fireplace in each of the two reading rooms, cypress woodwork, and lead pane “starburst” windows with “bull’s eye” centers.

On August 21, 1906, George Washington Brown spoke at the dedication ceremony in the Methodist Church across the street from the Brown Public Library. He recounted how as a boy he earned money “carrying passengers to funerals, tolling the bell for deaths and funerals, and driving the hearse.” When he was twelve, he said, he “performed the latter service when the remains of the lamented Governor Paine were borne to their last resting place.” Little did the twelve-year-old boy know that decades later he would erect a public library on the site of Charles Paine’s homestead.

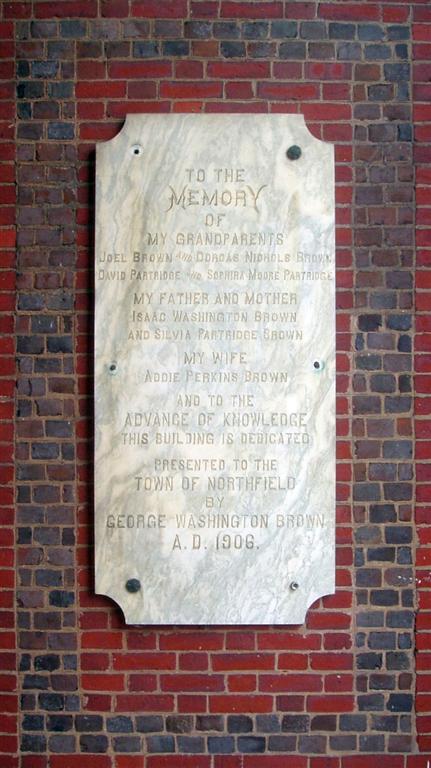

On the marble plaque at the main entrance to the library George Washington Brown dedicates the building to his grandparents, parents, and wife and “to the advance of knowledge”.

Ann Paine’s Painting of Northfield

Mary Ann Weeks was born in the last year of the eighteen century to Ezra Weeks and his wife of New York City. Her father was a successful architect and a member of the New York Academy of Fine Arts. Mary Anne received a good education for a lady of her social class, studying art, literature, and “some sciences”. In her late twenties, she married Martyn Paine, eldest son of Elijah Paine, prosperous owner of a woolen mill in Northfield. Martyn had received a medical degree from Harvard, practiced medicine in Montreal and then in New York City, where he became a distinguished physician and professor of medicine. He was involved in establishing the University Medical College, helped repeal a law forbidding dissection of human corpses, and published numerous articles and books on medical topics. Mary Ann employed her artistic talents by painting botanical illustrations for husband’s medical lectures and writings, such as his text Materia Medica and Therapeutics.

The Paines spent summers in Vermont and Maine. It was probably on a visit to her husband’s family in 1837 that Mary Ann painted this view of Northfield, which now hangs above the fireplace in the south reading room of the library. The red building at left center in the painting is the textile mill built by Mary Ann’s father-in-law, Elijah around 1812 for the stupendous sum of $40,000. Elijah owned a lot of sheep to supply wool, and the mill was a shrewd investment since war with Great Britain cut off the importation of woolen goods. The mill was powered by a log dam beyond the bridge crossing the Dog River, which flows through Northfield. The nearest white building on the right bank of the river is the Northfield House, a hotel erected in 1836 by Charles Paine, Mary Ann’s brother-in-law. The church at the far right is the Paine Meeting House, which Elijah built in 1836. Decades later the meeting house was cut in half and jacked up: a middle section was added and a hall was inserted beneath the structure, which today is the United Church

Mary Ann’s painting of Northfield hung in the “Ladies Parlor” of the Northfield House for many years and then was owned by various residents of the town until eventually it was donated to the library. In 1977, the badly darkened painting was restored by Tom Clark of Perkinsville, Vermont.

In 1850 the Paines vacationed with their son, Robert Troup Paine, in Wells Beach, Maine, where Mary Ann continued to pursue her interest in painting. (Wells Beach is still a favorite vacation spot for Northfield folks today.) A short while later, Mary Ann and Martyn endured a heavy blow when their son, a medical student at Harvard, died. Mary Ann, in chronic ill health during much of her adult life, did not long outlive her son, dying in 1852 of “congestion of the brain.” Her husband Martyn lived to be 83, dying in 1877.